The territorial configuration, the river network and the water basins of Bassa Romagna

The territory of the so-called Bassa Romagna historically coincides with Romagna Estense, which in the 15th and 16th century belonged to the Duchy of Ferrara, with Lugo as its capital city. The environmental conformation of this territory has been characterized, since ancient times, by a deep interaction of different environmental factors: inhabited settlements in areas dominated by still marshes or canal and river currents, which were a source of livelihood but also a life threat for the populations that lived along their banks. The landscape has always been shaped by an unstable hydrographic network.

Roman centuriation

When the Romans colonized Romagna, in order to organize the anthropization of the territory, they deforested the lands and channeled water into the area between via Emilia and the current via San Vitale, which partially overlaps with the old via Salaria. With the construction of the via Emilia (187 BC), which marked the beginning of the Romans’ colonization of the Po Valley, chosen for its agricultural potential, the Romans used a particular land measuring and division system (called limitatio) for the plain high-level areas, which led to the creation of centuria (the areas to be assigned), defined by coordinates called cardo and decumanus.

After hydraulic reclamation work, the resulting parcels (squares with sides of 710 m) were defined by draining ditches, which crossed with each other at a right angle, giving life to that regular draining network that is still visible in some areas, unaltered, well-functioning and corresponding with the road network. Via Emilia was the maximus decumanus; it was taken a reference for the division into new centuria: from Rimini the consular road joined the extreme part of Romagna with Piacenza, where the crossing across the Po river was located. The via Emilia developed along the foothill area, where cities were set up in connection with the beginning of the main Apennine valleys. Very few centres were born out of this axis.

A study carried out in the ‘60s by Lelio Veggi and Arnaldo Roncuzzi showed that there are still clear traces of the Roman Centuriation in the agricultural parcels of Lugo and Bagnacavallo. The study also shows that the degradation of some areas is due to the rising level of the water table, which has caused the development of swampy areas, as well as the layering of alluvial deposits generated by the frequent river overflowing during the Middle Ages.

Hydrography

Rivers, those majestic traces of life, “have been designing” the Romagna plain: human beings have used their water to reclaim the land, they have risen their level to offer more space to agriculture and have well-kept fields, which are accurately defined by a thick network of ditches and channels. In the western part of Romagna are the rivers Lamone, Idice, Sillaro, Santerno and Senio. Born on the Apennine mountains, they flow down from parallel valleys towards the plain and then to the sea. Characterized by being torrential streams with an irregular flow, in ancient times they used to flow into the wide lagoon that separated the coastal area from the foothills inland, where a lowland forest developed.

The Santerno-Senio river, Vatrenus as Pliny called it, for a long time was a tributary of the Primaro river (southern branch of the Po river). It divided the large valley into Libba in the west and Bartina in the east; it characterized the territory with its irregular flow. In the late middle Ages, with a reclamation intervention and hydraulic works, the rivers were deviated more to the west. In particular the Senio-Santerno river: it was channelled more to the west, towards a location called Bastia; the Senio river was directed from Cotignola to San Potito and Fusignano towards the Po di Primaro river, whereas near Boncellino, the Lamone river was channelled into the abandoned riverbed of the Senio-Santerno river.

From via Emilia, the main connection road between the east and the west, direct road connections led to river and floodplain ports. People and goods were transported through navigation on small vessels. The boats were towed up river, guided and rope-dragged by draught animals positioned along the banks. This ancient technique was already exploited by the Romans, who used it to build via helciaria, which ran along the rivers and could be used human and animal dragging.

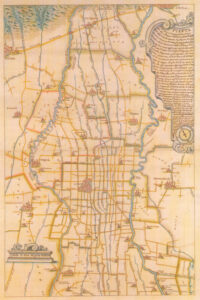

Bassa Romagna del Ducato di Ferrara

Mappa redatta da Luigi Manzieri nel 1750, Biblioteca Comunale Ariostea di Ferrara

(tratta da libro “Le bonifiche in Romagna” di Tito Menzani).

The Senio and Santerno rivers, which flew into the Po di Primaro river, put into communication the Po river plain with the sea. Along their path were: the port of Conselice, Caput Silicis, in Santa Maria in Fabriago; the port of Pedretolo, in the north of San Lorenzo di Lugo; the port of Catena, at the Pieve di Santo Stefano in Catena; the port of Maiano, near the current location of Maiano Monti; the port of Fenaria and Libba near Fusignano and the port of Bagnacavallo. This port network allowed traffic flow between Ferrara and Veneto areas with Romagna and the Tuscan foothills, as indicated by Riccaldo Ferrarese with his maps on Charonico parvum.

Little ports, functional to market activities and medieval exhibitions. The local communities integrated the natural waterways with the construction of canals for supplying water to mills, on which they claimed public rights and tax revenues. Many bastides and guard towers were built in 12th and 13th centuries in strategic points along navigable waterways, with the aim to safeguard them and make the collection of taxes and concessions easier. The Canale dei mulini di Castel Bolognese, Lugo e Fusignano and the Canale di Imola and Massa still survive in the contemporary landscape and are living proof of history, just like some “serpentine ways” that in the past ran along the waterways, but which have now disappeared. Also the Collettore Zaniolo, that is now mostly channeled and collects the wastewater of the Imola plain area, was used as a waterway together with The Cavo di Gambellara.

Some relevant interventions were made under the Este’s domain (15th and 16th centuries), to establish a direct communication between Lugo and Ferrara. They interrupted the Santerno river in San Lorenzo in order to direct it into the Po di Primaro, with a new 12 km-long channelling. The Estes also built the road that used to connect Bastia dello Zaniolo with Bastia di Ca’ Lugo, which was used to defend a crossing point on the Santerno river. In the 15th century the road took the name via della Bastia.

Many docks remained active until mid 15th century, when the wet lands were reclaimed.

From the beginning of the 16th century till the end of the 18th century, the territory became more agricultural thanks to the drying up of large areas and the reclamation work conducted on those areas that used to be flooded. The consistency and functionality of the waterway system was reduced. As a consequence, the navigation inter valles between Bologna, Conselice and Ravenna was hindered.

Moreover, the old Po di Primaro river was progressively suffocated by the mud coming from the Apennine rivers; nevertheless transportation along internal waterways connected to the Po or the Reno river, previously called Primaro, continued for a while before stopping forever. Two notifications dating back to 1809 from the Podestà of Faenza about the transit and unloading of wheat make explicit reference to the “Canale Naviglio Zanelli” and the Naviglio Warehouse located at the dock of Bagnacavallo”. A few decades before, as requested by Earl Zanelli, a Canal (named after the Earl) was built in order to connect Faenza with the sea: the canal took the water from the Lamone river, flew into the Reno river and then reached the Adriatic Sea. Mills and turning bridges were built on the Canal; poplars were planted on the banks to get timber. The goods were loaded on barges and then they were rope-dragged by couples of horses from the banks, transporting grains, flour, timber, marshland herbs and wine. With the introduction of the railway in 1860, progressively the canal was not used for navigation and transport anymore, but only to feed the mills.

A private agreement dating back to 1821 looks very interesting. It was signed by a tradesman in Lugo, who was concluding a sales contract for 500 wheat bags, whose transport depended on the navigability conditions of the Santerno river: in order to load the first quantity of bags it was necessary to “find a place at Bastiglia or Chiavica di Legno”; it also says that other bags navigating along the Canal of Fusignano had to be unloaded “in front of Calcagnini mill”. The goods route, that can be inferred from the many maps kept at the archives of Ravenna and Ferrara and which refer to the land between the Santerno and Senio rivers, shows that the Santerno flew into the Primaro river and the Canale dei molini ran near the Port road. The entire journey of Canale dei molini is shown, including when it enters the valley, crosses it and leaves it as Canal Vela, up flowing into the Reno river at Passetto. In Taglio Corelli, when Canal Vela became the collector of “Congregazione delle acque” – for the territory between the Santerno and the Senio river – the Canale dei Molini was channelled into the dead riverbed of the Santerno river and let it flow into Po di Primaro through the Napoleonic lock called “I chiaviconi della Canalina”. By means of Vinciane locks, it used to protect it from the river floods.

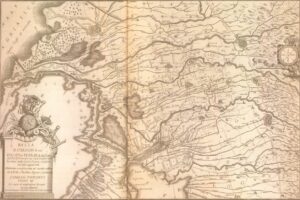

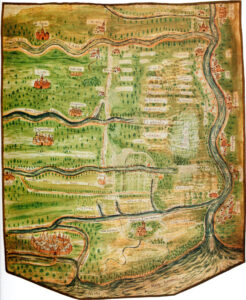

Territory between the river Po di Primaro and Ravenna, Modena Historical Archive, Estense map, Vol. 6 pag. 131 sec XVII

Reclamation work

The following are examples of the history of places, where the network of watercourses determined man-made choices and left indelible marks on the territory. I.e. the regular reclamation pattern, with regenerated land and drainage canals in many parts of Bassa Romagna. The reclamation interventions were conducted next to the local roads, which in their turn match with the old towpaths, used for the towage of small boats.

On the edge of high and well-drained lands, the frequent floods of the watercourses left alluvial deposits and caused a different fertility of the soil, resulting into a different agricultural potential and vocation. In fact, between the end of 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, the agrarian landscape changed significantly: beside the old parcels cultivated with sharecropping, the landscape started being characterized by large arable lands subtracted to the water, where rise fields were widely spread.

Plan of part of the Ravenna area with the Ferrara area from the Conselice valley to San Biagio al mare, between Ravenna and the left bank of the Reno river and the Po di Primaro. State Archives of Venice, Savi and performers at the waters, Po series, dis. 177

In order to complete the reclamation of the territory, and with the aim to give work to local labourers (called “scariolanti”) in 1903 the Canale in destra Reno started being built, locally known as “Drainage of fresh water”. The embanked canal, originates at Botte Selice del Collettore Zaniolo and collects the water of hydraulic Consortia Zaniolo, Buonacquisto, Canal Vela and Fosso Vecchio included between the Sillaro, Santerno, Senio and Lamone rivers, and then after 37 km takes it to the sea, running over the old Lamone riverbed in the last stretch. The Canale di Bonifica (Canale in destra Reno) follows a parallel route on the right-hand side of the Reno river, at a lower level, in order to collect the low-lying water from the rivers. These watercourses, as a matter of fact, are at a higher level than the territories they run through. They flow into the Reno-Po di Primaro. During the construction of the Canal, some masonry work was built at the river intersections: three spans for the Santerno river, five for the Senio river and the Canale dei molini.

Today, in our land, where the difficult relation with water seems to be over, the Consorzi di Bonifica (Water Reclamation Consortia) act in order to maintain these results and guarantee a correct water management.

Toponomy

The Senio and the Santerno river, with their active and dead courses, the Naviglio and Canali dei Mulini suggest interesting facts from the historical, economic and environmental point of view. The itinerary that starts in Lugo and develops along roads and embankments invites us to focus on place names, taking us far away into the history of places and landscapes, along memory lane.

First of all via Padusa reminds of the big lagoon at the mouth of the ancient southern branch of the Po river, Padus, which separated the sea from the water expanse behind. A transition system between the land and the sea, fed by the Po river and the Apennine rivers that flew into it.

But there are many other names that make reference to the presence of water: along the route is via Canaletta, making reference to a limited-sized water canal that used to run in that area; while Canalazzo and Fiumazzo, used with a pejorative meaning, take us to dead watercourses that have lost their functionality nowadays. Place names like Coronella and Roncadello instead narrate about the hard work of the land: the first refers to a bank set up in order to create a border with the marshes and counter the floods; while the second name etymologically originates from runcus, meaning the reclamation of uncultivated and forest areas with pest control operations. Last, Manzone refers to the land resting from cultivation or a cleared forest, used for free cow grazing.

Lugo

Located in the northern part of the fertile plain between the Santerno and the Senio rivers, it is characterized by a thick network of natural and artificial canals (among them Canale dei Molini di Castel Bolognese), resulting from the reclamation work that shaped these lands. It is difficult to identify the origin of Lugo, actually this has been the subject of debate over the years, but certainly thanks to its geographical position, already from the Roman time and the Early Middle Ages it was a central part of the Roman centuriation. Moreover it could count on parish churches as important players for territorial supervision and a wide hydrographic basin.

The name Lugo may find its origin in Latin lūcus, religious or sacred wood, or from Celtic lug or luc meaning village, suggesting the presence of ancient settlements, especially after the findings occurred in 1982 in the caves of the local furnace. Anyway the Roman colonization of the Lugo territory, located on the 20th decumanus in the heart of the centuriation, is due to the position of the via Emilia and the fact that the high-level and dry areas on the edges of the marshes were given to settlers and turned into agricultural land.

The central role of Lugo is highlighted also by the urban topography, based on a centuriation axis around which the medieval town developed. The axis that crossed the inhabited centre, nowadays occupied by Quarantola Felisio provincial road, used to connect the port with the parish Church San Giovanni in Libba. The city, located in a favourable position with respect to via Emilia in the east-west direction and north-south, took advantage of the salt trade coming from the city of Ravenna and Cervia towards Bologna, as well as being a meeting point between the Po plain hydrographic basin and the Trans-Apennine territories. Another growth factor was the proximity with small floodplain ports, which bordered with the dry land and therefore were particularly favourable for road transport and for the birth of local markets. As well as being at the centre of the food supply trade, Lugo benefited from the presence of local religious institutions from Ravenna, which worked to increase agricultural production that became complementary to an economy based on forestry-pastoral, hunting and fishing resources. These factors consolidated exchange and trade, leading to the creation of an agricultural market regulated by constant deadlines, further developed and consolidated thanks to the presence of a wide Jewish community.

Going back over the centuries in order to find its origins, Lugo does not appear as a driver centre during the Early Middle Ages – differently from the parishes nearby, such as Bagnacavallo, San Giovanni in Libba in Fusignano or Santo Stefano in Catena. Nevertheless, Lugo starts appearing from the 12th century, with reference to some land subdivision of Massa Sant’Ilaro. The first document (dating back to 1081) refers to the first settlement which evolved from being a villa, without defence, to a village and then a fortified garrison, castrum.

The importance of Lugo and its dignity as a castrum, with its own territory, are referred to by Descriptio Romandiole, the census of Romagna drawn up in 1371 by Cardinal Anglico Grimoard. When, towards the end of 14th century, the Lords of Ferrara conquered the heart of Romagna with the power of money, Romandiola became Romagna degli Estensi (Este’s Romagna), and it remained so until the end of the 16th century.

Already in 1376 Niccolò II was the Lord of Lugo, but the final passage to Ferrara domination occurred with Niccolò III in 1437, when Lugo, at that time the capital of Romagna degli Estensi, played a primary role by annexing the surrounding territories, among which was Zagonara, after its village and castle destruction by the Milanese, that had fought against Florentine.

The Este’s season paved the way to a new phase of land reclamation work, aimed at stopping the expansionist ambitions of Venice and safeguard trade between Ferrara and Lugo. With Duke Borso, in 1460 the Primaro del Santerno river was straightened and diverted; the Senio river was diverted and the land between the two rivers was cultivated. The territory ruralisation led to a steep demographic growth and the birth of San Bernardino and San Lorenzo villages, which paved the way to a further demographic wave and the birth of other inhabited centres in Belricetto, Giovecca, Frascata, Lavezzola.

Also after the end of the Este’s domination, in 1598, with the return of the Papal government, during the Legations period, Lugo had to take care of water control, as a necessary and urgent intervention due to frequent floods and overflows that took place during the 17th and 18th centuries. Studies and projects for improvement of the Reno, the Senio and the Santerno rivers, which with frequent floods had contributed to the formation of San Bernardino and Passetto valleys, were proposed to the Sacra Congregazione delle Acque, which supervised the work.

With regard to water issues, the Canale dei mulini, in Castel Bolognese, Lugo and Fusignano, was built in the 14th century. It took its water from the Senio river in order to ensure suitable hydraulic power to the local mills for grain grinding. It kept this role until the arrival of electric power; over the centuries it fed many plants and was often at the centre of fights and litigations. Once it stopped being used for grinding, the Canal started being used (and still is) for irrigation purpose in agreement with CER, Canale Emiliano Romagnolo. It crosses the plain from Tebano sul Senio lock and, after running for around 40 km, it flows into the Canale in destra Reno in Taglio Corelli area. It belongs to the hydraulic network, it is managed by Consorzio di Bonifica della Romagna Occidentale (which manages all the territories upstream via Emilia until the Apennines) and it represents a natural connection between the Hills of Parco della Vena del Gesso and the wet plain of Parco del Delta del Po (Po Delta Park).

Massa Lombarda

The reclamation of the swampy areas, which took place between the 19th and 20th centuries, was fundamental for the agricultural development of Massa Lombarda, which mainly focused on orchards and the construction of fruit and vegetable warehouses. In fact it is known as the “village of fruits” and in 1927 it hosted the II° National Expo of Fruit farming.

The name explains its origin: massa Sancti Pauli, an agricultural settlement at the border with the Lugo forest, specifically a group of agricultural fields with a church dedicated to St Paul.

It was called Massa Lombarda in 1251, when many families arrived from Brescia and Mantua, fleeing from intimidation by Ezzelino da Romano. The new settlers received the land, subdivided into regular squares, in exchange for their commitment to reclaiming and farming it.

In Massa Lombarda we are taken back to a reality that is marked by water flowing: the atmospheric setting of the old wash house, fed by the water of Canale dei molini of Imola e Massa. Today it is a place hosting theatre performances, narrations, music, poetry and dance. The Canal, stretching for around 40 km, starts from the Santerno river and, after going around Imola, it touches upon Bubano, San Patrizio, Conselice, Lavezzola. It flows next to via Selice, until it flows into the Reno river near the so-called “della Bastia” bridge. At the moment it takes its water only up to Massa Lombarda, where one branch feeds the public wash house, while another branch detaches from the main river before the inhabited centre and goes back to the Santerno river. It was built during the Early Middle Ages by the Benedictine monks of Santa Maria in Regola monastery. They constructed it in order to carry out a reclamation of the low-lands, but also for navigation purpose, to feed several mills and irrigate the fields.

San Patrizio

San Patrizio, a hamlet in the municipality of Conselice, located along via Selice is an ancient territory, whose baptismal little church dates back to 1092. Located around the hamlet, the village of San Giovanni in Pentecaso had been built previously. Maybe it was a Lombard-origin settlement and for this reason it was called Masa dei Lombardi, as Claudia Pancino writes on her essay about the situation of Conselice from the 11th to the 14th century. San Giovanni in Pentecaso, due to its position between the woods and the valleys, was often the reason for fight between the municipalities of Conselice and Massa Lombarda.

The settlement of San Patrizio, located at a higher level and therefore less exposed to water and flood risk, gave shelter to the the inhabitants of Conselice during of the frequent floods of their land. Exactly in the first half of the 15th century, when it joined Conselice, San Patrizio gave up its administrative independence.

San Patrizio boasts the presence of a mill built towards the end of the 15th century above the Canale dei Molini di Imola, the ancient higher-level watercourse that from the old Forum Cornelii joined its water with the Po di Primaro river. The mill, consisting of an original building with a rectangular layout, stands over the canal with two arcades. Even if it still keeps the old equipment, the mill had to undergo substantial restructuring and extension work in the ‘50s.

Conselice

The territory of Conselice, located at the centre of a thick hydrographic network, is characterized by a thousand-year-old relation with river water and the wide low-lying areas. Located between the Sillaro river in the west, the Reno river in the north and the Santerno river in the east, it is crossed by Canale Zaniolo, a wide collector that comes from Mordano, after running through the Imola territory with Cavo Gambellara running parallel to it. In Conselice, they join together and flow into Canale Destra Reno at Botte Selice. Then they continue until reaching the Reno river. The territory is also characterized by Canale dei Molini di Imola, which was used for goods transportation and for powering several mills.

The first settlements of the area between the Sillaro and Santerno rivers were located on higher-level and drier spaces created by alluvial deposits, but at the time of the Republic of Rome, in the 2nd century B.C., the territory was subjected to reclamation work and water regulation through the centuriation system, the ancient Roman agrarian subdivision, which divides the land into squares in order to distribute properties to the settlers and which is still visible today. The system was also functional to water flows. Via Emilia was considered as the decumanus maximus; via Selice was cardo maximus.

With regard to the birth of Conselice, a document dated 5th June 1084 can be taken as a reference; it indicates Portum Capitis Silicis. Its growth as an inhabited centre is confirmed by a later source from 1151, where the village is referred to as castrum et curtem, with marshes and piscarie. The document of 1084 mentions the negotiations between the Bishop and the city of Imola related to the taxes on goods transiting by land and the collection of taxes at the port. Conselice was the port of Imola by means of a canal, called Poi dei Mulini, which ran along via Selice and then entered the floodplains, valles iuxta Padum, and then reached Po di Primaro, the waterway which joined Ravenna, Ferrara and then went up to Piacenza.

It is a territory with diversified and documented landscape aspects: in 1435 there was documented presence of meadows, woods, forests, marshes, backwaters, floodplains and piscarie, namely areas where it was possible to graze, hunt and fish. Therefore there were different environments, certainly productive and offering sources of livelihood and work. Between the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century, valleys, rice fields and small farmed fields were reported to be present. Wild woods and large unfarmed spaces, populated by animals, foxes, wolves and boars progressively pushed the community to convert unfarmed lands into farmed lands as a consequence of reclamation interventions. Besides, in the same years, the backwaters and non-productive lands started hosting rice fields, with the objective to make use of the lowlands for the cultivation of cereals. And right in the rice field water in Conselice, frogs started being bred. This granted the village the name “the land of frogs”.

Toponymy, iconographic signs and some monuments narrate the multi-annual history of a landscape that has always been balanced between water and earth: via Cantalupo Selice, near Conselice, reminds of the wide woodlands inhabited by wild animals like the wolf; the Municipality coat of arms where, on a light blue background, appear the tench and the pike, recalling fishing in the marshes; an usual monument to the frog is located at the centre of the village entrance roundabout; the sculpture dedicated to mondine (rice field workers) and “scariolanti” in the public park, pays tribute to the many labourers, symbol of work and social redemption. In fact they worked very hard to build the river banks, canals and were employed in the rice fields. The sculpture was inaugurated on 3rd May 1990 on the occasion of the one-hundred-year anniversary of the mondine’s fights and protests which ended up in the notorious massacre of 1890. After that tragic event, a cooperative was set up to join the labourers of Conselice, Lavezzola and San Patrizio, which over time progressively rooted in the territory and paved the way to the deep economic and social redemption of the population. In 1919, as deeply wanted by Nullo Baldini, the Federazione delle Cooperative di Ravenna purchased Massari estate, previously owned by Massima Zavaglia family of Ferrara, who had farmed rice in those low and wet lands. The new Cooperatives started a significant reclamation activity on those wet lands, by draining and improving the land conditions to start farming dry crops.

Today Cooperativa Agricola Braccianti Massari, born out of the merger with other CABs (Cooperativa Agricola Braccianti) in 1997, is a large agro-tourist company, which has joined agricultural activities with tourism and catering, keeping the tobacco plant and rice production as testimonies of the past. The recovery of a floodplain area, nowadays enjoyed by people in their free time and a perfect environment for resident and migratory bird life, recalls a landscape characterized for centuries by the coexistence of earth and water.

Lavezzola

The village of Lavezzola was born in the 15th century as a feud given by the Estes to Giacomo of the noble Lavezzoli family, who gave his name to the village and left long-lasting traces. The territory in concession, located between Po di Primaro and Frascata, was functional to guaranteeing the security of the northern borders of Romandiola on the right bank of Primaro, guarded from Bastia dello Zaniolo.

Lavezzola lived in symbiosis with the Primaro river, flowing in the north and the floodplain landscape that, from the right-hand side of the river bank used to bend to the south, where the Senio and Santerno rivers joined together. Seasonally, the land emerged and filled the backwaters with debris.

The “extremely muddy” Santerno river, with its bends, was useful for land reclamation. Canale Zaniolo, wide and with a large capacity, was used for navigation and milling. According to hydrologist Aleotti, twenty mills used to grind in 1565 along its route. Its name seems to be linked to miller Martino, mentioned by a notary deed of the 14th century that refers to fossatum Martini Zanioli. Further evidence confirming its navigability is the presence of a chain on Zaniolo, a barrier, a “checkpoint” at Bastia for tax collection and to fight against illegal traffic. For centuries the Primaro river was dominating; it was a sort of road artery with its watercourse and high-level banks, dry and easily viable, positioned above the low-level surrounding marshes. The first inhabitants, devoted to fishing and hunting, had the right to protect themselves (diritto di frasca) in the wood. Hence the name Frascata. In order to carry out their first agricultural activities, actually on very few lands, they used the river water. Gradually they dried the wetlands and, with deforestation, also the wood areas were cleared.

Just like other villages in Bassa Romagna, Lavezzola, now a hamlet of the municipality of Conselice mainly devoted to agriculture, went through different phases in its antrophization process: from a swampy area to a villa with little settlements that gradually developed and took the shape of a small urban centre.

For the community, regardless of the Lavezzoli, Bentivoglio and Papal Legates who governed the area over the years, the problems were always related to water, to the many floods that every year covered the fields, the crops and hindered the grinding business. Straightenings, regulation works, deviations, embankments went on for centuries with disputes and attempts to solve the water issue once and for all. Finally the solution came with the Reno river flowing into Po di Primaro, obtained with excavation and reinforcement of the riverbanks with an autonomous mouth in the sea built at the end of the 18th century.

Vallesanta

The Campotto valleys (FE) are protected wetlands, born as a consequence of the Primaro river floods during the Late Middle Ages, when the river used to flow at a higher level and did not get flood water from the Apennine muddy streams. Residual of the previous marshes, divided into three communicating compartments, the valleys act as flood retention basin. After being collected, the water is then re-introduced into the Reno river by using pumps. The area of Vallesanta, between the Idice and the Sillaro rivers, is characterized by submerged hygrophilous vegetation and, in a small area in the south, by a wet meadow, inhabited by birdlife. Today these environments engage us emotionally with their undisputable charm, which is even more atmospheric with autumn mist or bright colours at sunset.

Santa Maria in Fabriago

Ancient village in the municipality of Lugo, it is located on the left-hand side of the Santerno river. Just like the near village of Campanile, it was part of the parish church of Santa Maria in Centumlicinia-Centum Lisinia, that only in 1091 took the name Santa Maria in Fabriago.

The proximity of the small floodplain harbour of Petrodolo, which put into communication the territory with the Primaro river, was a vital trade centre. It still reminded by via Predola, which runs across Fabriago countryside and whose name is connected to the ancient harbour of Petrodolo or Predolo. Centumlicinio-Centum Lisinia may come from centum, the parts into which centuria was divided or it may originate from the term Licinia-Centum lacinium, a fragment of the centuriation, referring to an undivided and not allocated land, which was used for grazing and timber production since it was not farmed. Surrounded by water, in the 8th century the territory of Fabriago was a fundus mainly inhabited by families devoted to fishing and hunting. Around the middle of the 13th century, the community of Fabriago accepted to be acquired by Lugo, which enlarged its territory incorporating also San Bernardino.

The name Santa Maria in Fabriago is quite recent and refers to a territory that was once called Bruciata or Brusata, named after the land of a certain man called Brusatus de Fabriaco (1188). After the channelling of the Santerno river in 1460, as a reference to the river that crossed it, the territory took the name of “Brusata di qua” and “Brusata di là”. Near the left bank, at a higher level than the surrounding land, a fortified bastion was built, with an inhabited village all around it.

The Church of Campanile in Lugo is what is left of the plebato (parish) of Santa Maria in Centumlicina, later called Fabriago. With its high bell tower, its architectural style is similar to the bell towers from Ravenna, dating back to the 10th and 11th century.

The story of Fabriago is very emblematic of the relation between earth and water, hostile to human settlements, but essential for the survival of the economy and functional to traffic and commercial trade. After the year 1,000, Fabriago became a flourishing castrum, but already towards the end of the 12th century it suffered from a new hydrogeological crisis that caused a comeback of unfarmed lands and marshes. As a consequence, the inhabitants moved towards more flourishing and welcoming lands, leaving a desolated, frequently flooded territory, with an un-kept and ruined church that is represented today by the tower, which gives its name to the inhabited centre.

Torre, a location near Santa Maria in Fabriago, takes its name from an ancient woodland which belonged to Lugo, surrounded by the flood water of the Santerno river. There was a tower, which has disappeared. As a confirmation of the tower that rose as a lookout post on the surrounding territory, is a quote of a tavern called “Hostaria della Torre” that was destroyed by water in 1403. Following the historical events and the ownership changes, it is possible to find trace of it in 1598 and then in 1764, when it was finally closed due to the fury of the flood water.

San Bernardino

San Bernardino is a small residential and agricultural area in Lugo countryside, on the right side of the Santerno river following the river bends.

San Lorenzo

The first reference to this hamlet in the municipality of Lugo, located along the Santerno river banks, dates back to the 15th century. At that time, with the new river route and the parallel road running towards Ferrara, new settlements were built. Among them was the village and the parish of San Lorenzo in Selva and, more in the north on a river ridge was San Bernardino in Selva.

Via Fiumazzo, previously called via del Fiunazzo, old riverbed of the Santerno river, starts in San Lorenzo and runs across Torre and Belricetto until Passogatto. Its name explains the transformations related to the river and the human interventions.

Ca’ di Lugo

As part of the Este’s family reclamation interventions carried out in the 14th century, the Santerno riverbed was channelled and directed into the Po di Primaro. As a result, new inhabited centres were born on its banks, among which: Ca’ di Lugo, in the crossing point between the new road built by the Este’s family and the Santerno river.

Do you want to explore these lands? The “Earth and water” itinerary is perfect! Click here for more information